35+ Important Archeological Finds That Gave Us Invaluable Insight Into Our Past

History has shaped the world as we know it today, and it will continue to be so for many centuries to come. We know it’s obvious, but it still is worth repeating.

The best job of preserving human history’s archives has been done through written tales and well-known artifacts. Famous antique relics can help corroborate historical facts and settle disagreements because you can’t alter the past. Because of this, many historical items are simply priceless.

But what exactly makes an artifact so renowned and precious? The most well-known artifacts are those from long-dead cultures that significantly impacted human history. Many of these, including paintings and bells, are regarded as cultural treasures due to their importance to the local population. When you piece them all together, they give us a glimpse at the cultures that produced them and of humankind as a whole.

The Antikythera Mechanism (205 B.C. – 100 B.C.)

The Antikythera Mechanism is as mysterious as it gets. It is now widely accepted that the Antikythera device was the very first computer. It was discovered at the bottom of the ocean, and despite decades of research, a number of its capabilities are probably still unclear.

The device’s many clock-like cogs and gears are believed to produce a mobile, hand-cranked, Earth-centered orrery of the heavens that indicates better star and planet placements in addition to solar and lunar eclipses. These findings are from the X-ray scans of the object.

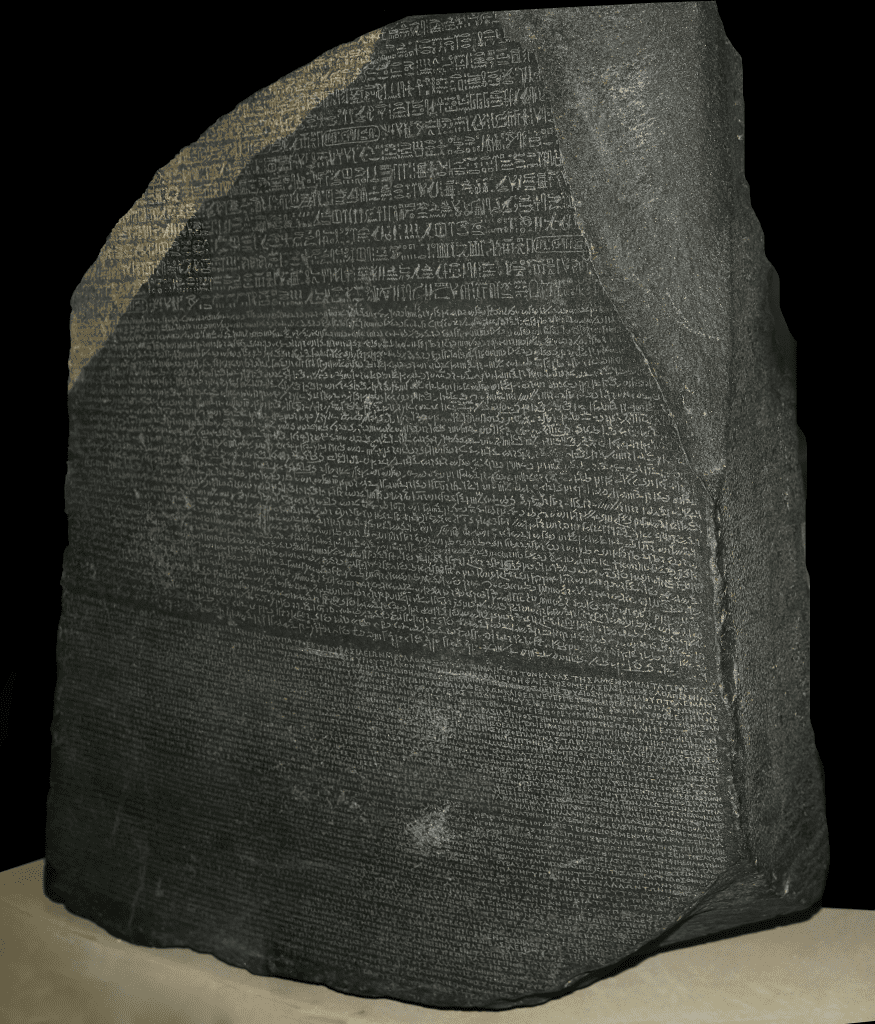

The Rosetta Stone (196 B.C.)

The Rosetta Stone is an inscribed decree attesting to the benevolence and piety of Egypt’s ruler Ptolemy V, which was declared in 196 B.C. by a gathering of Egyptian priests. There are three writing styles on the stone: Hieroglyphics, Demotic and Ancient Greek.

The stone is a crucial tool in aiding academics in their understanding of the long-forgotten language. The main reason was that after the 4th century, hieroglyphics were no longer used. Therefore, the system of writing was a mystery to academics.

Remains of an Australopithecus (3.2 MYA)

Lucy is an almost complete skeleton of Australopithecus afarensis. She was discovered in 1974 at the Afar Locality (AL) 228, a location in the Hadar archaeological area in the Afar Triangle of Ethiopia. She was the first fairly complete skeleton retrieved for such species.

In Amharic, Lucy is known as Denkenesh. The remains are roughly 3.18 million years old! She is an important contributor to our knowledge of human beginnings and advances evolution. Lucy’s skull and other bone pieces amount to about forty percent of a female hominid.

Aztec Sun Stone (15th Century A.D.)

The five periods of the sun of Aztec legend are depicted in the Aztec Sun Stone, sometimes called the Calendar Stone. The stone had been a component of Tenochtitlán’s Temple Mayor’s larger architectural ensemble. The Aztec Sun Stone features images of the five succeeding Suns from Aztec mythology.

This object was created around 1427 CE. The basalt rock weighs 25 tonnes, with a diameter of 3.58 meters, and a thickness of 98 centimeters. 174 years after its rediscovery, it found a permanent home at Mexico’s National Museum of Anthropology.

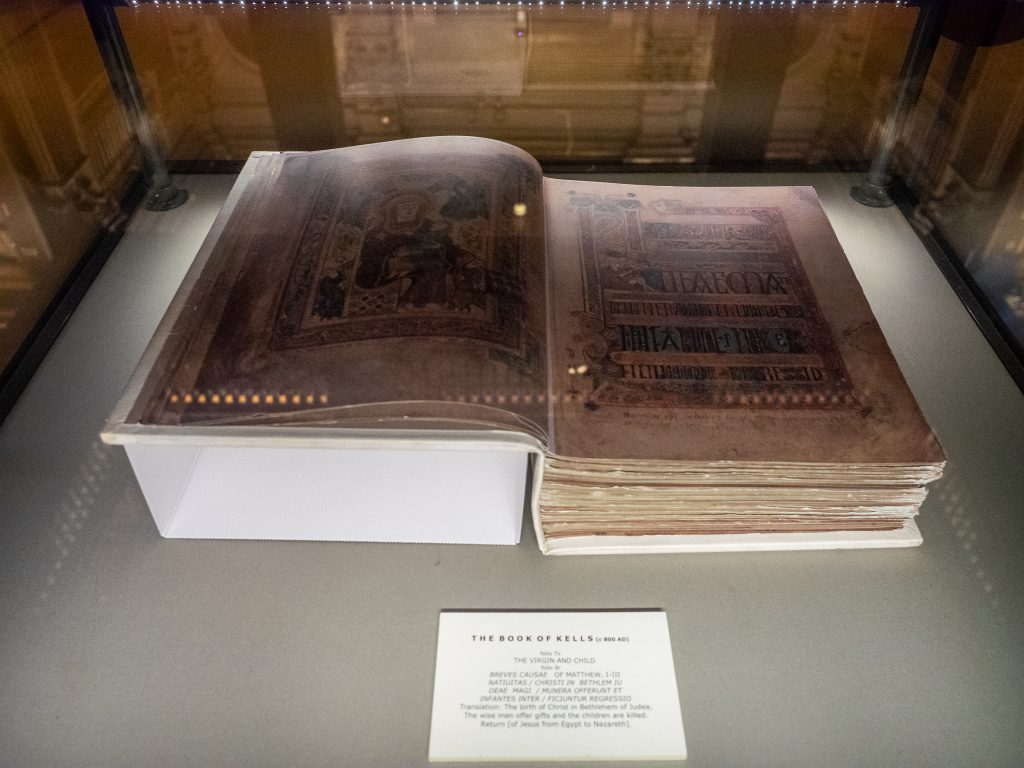

The Book of Kells (9th Century A.D.)

The Book of Kells is currently kept at Trinity College in Dublin, Ireland, and dates to around 800 CE. Due to the intricate, meticulous, and majestic nature of the images, the book is the most well-known of all medieval illuminated manuscripts.

Captivating drawings of humans, legendary creatures, and Celtic knots can be seen throughout the book’s pages. Since the artwork was clearly given more consideration than the text, it is believed that the book was produced as a display piece for the altar rather than for everyday use.

Tutankhamun’s Mask (1323 B.C.)

Tutankhamun’s Mask is one of the most well-known artworks in the world. It is currently on display at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. The artwork was created by an artist using a wide range of materials, including lapis lazuli and amazonite.

The mask’s flawless, brilliant gold face is designed to resemble the young pharaoh. The funeral mask of King Tut, which was initially carefully placed directly on the mummy within the innermost gold casket, is meant to help the departed young pharaoh’s spirit identify his person in the underworld.

The bust of Nefertiti (1345 B.C.)

Despite having been discovered alongside sculptures of other members of the royal family, the Bust of Nefertiti is undoubtedly the most well-known work. The Bust of Nefertiti is, as the name implies, a sculpted bust of Queen Nefertiti. She ruled beside her spouse Pharaoh Amenhotep IV.

Pharaoh Amenhotep IV was afterward renowned as Akhenaten. The bust is among the most famous artifacts that represent ancient Egypt. It was found in the studio of Thutmose, a well-known and talented sculptor who produced plaster representations of the royal family.

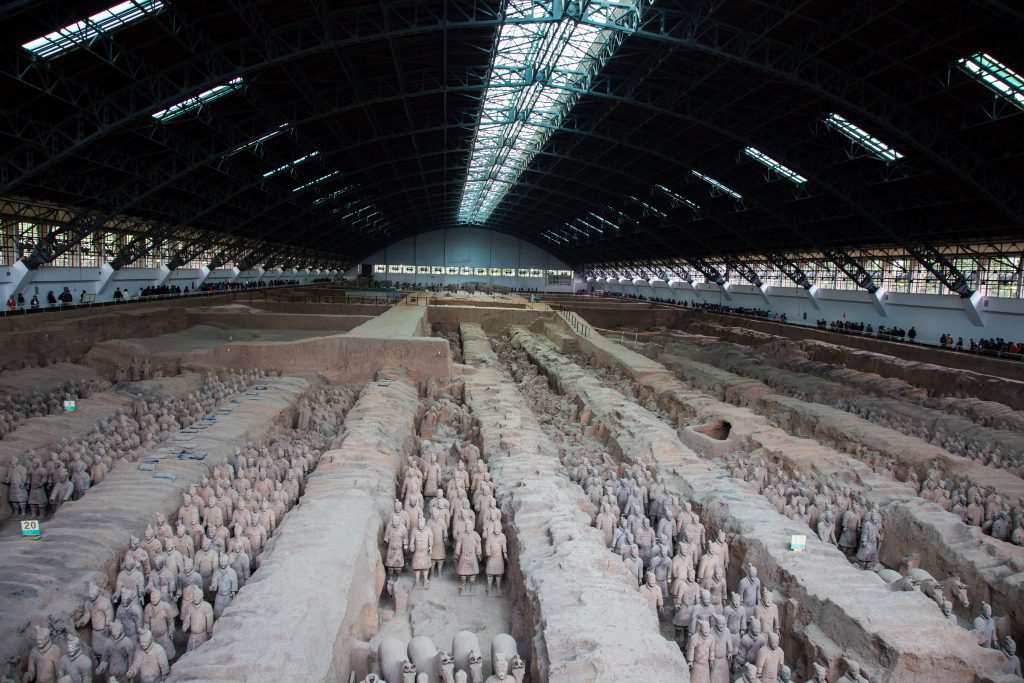

The Terracotta Army (246 B.C. – 209 B.C.)

Like many other historical artifacts, this funerary gift was meant to guard a coffin—that of Emperor Shi Huangdi, the first emperor of China and the creator of the Qin dynasty. The term “Terracotta Army” describes the tens of thousands of life-size clay replicas of soldiers, horses, and chariots.

These life-size, incredibly convincing clay soldiers even held working weaponry until curators switched them for their own safety and preservation. An estimated 700,000 workers slaved away to create the intricate army, complete with realistic faces and soldiers of all ranks.

The Oseberg Ship (820 A.D.)

The Oseberg ship’s snakehead bowhead is a well-known global representation of the Viking Age. Since she was discovered in 1904, in the vicinity of Tonsberg, the ship has been veiled in mystery. The elaborate, oak-built Oseberg ship was a Viking vessel that could either be rowed or sailed.

It was found in a sizable burial site at the Oseberg farm, close to Tansberg. Estimates place the year of construction around 820 in what is now Norway. It’s one of the most exquisite and perfectly preserved Viking items ever discovered.

Nok Terracottas (500 B.C. – 200 A.D.)

The oldest surviving expressive sculpture south of the Sahara was discovered in 1943 while mining for tin at the hamlet of Nok. It was a clay head. Complete Nok heads are held in high esteem since erosion has degraded numerous sculptures to pieces.

Other than the coils inside, the majority of Nok sculptures are hollow. The millennia-long durability of such ancient items, which were expertly crafted using native clays and gravel with a robust composition, is a monument to the skill and technique of their creators.

The Nebra Sky Disk (1600 B.C. – 1000 B.C.)

The Nebra Sky Disk is a valuable piece of evidence showing old cultures’ understanding of astronomy. This bronze disc dates back to 1600 BCE date. It is blue-green patinated and imprinted with signs made of gold leaf that appear to be a crescent moon.

There’s also the sun (or possibly a full moon), constellations, a curving gold band that is taken as a sun boat, and an additional gold band on the edge of the disc that likely represents one of the horizons. The opposite side is missing another gold band.

The Ram in a Thicket (2500 B.C.)

The Ram in a Thicket, which is often referred to as “Ram Caught in a Thicket,” is one of two identical statues that were discovered in one of the tombs in the Royal Cemetery in Ur, southern Iraq, in 1928.

The archeologist who discovered it was also an expert on Mesopotamian ancient art. The figures are thought to have been built between 2600 and 4000 BCE. For its period, Ram in a Thicket indicated advanced metalworking skills. They were crafted using materials like copper, wood, lapis lazuli, and gold.

The Mask of Agamemnon (1550 B.C. – 1500 B.C.)

One of the most iconic gold items from the Greek Bronze Age is the “Mask of Agamemnon.” It was among the many gold burial masks—masks placed over the faces of the deceases—discovered by renowned archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann. They were laid in the shaft graves of a royal cemetery.

The graves were found at Mycenae in 1876. The most intricate and aesthetically distinctive mask became renowned as the “Mask of Agamemnon,” after the illustrious ruler of historic Mycenae. Agamemnon’s victories and hardships are lauded in Homer’s epic poetry and in Euripides’ tragic tragedies.

The ruins of Akrotiri (1500 B.C.)

Among the most significant ancient cities in the Aegean civilization was Akrotiri. The site has been inhabited since at least the 4th millennium BC. In the 3rd millennium BC, a sizable colony was founded, and between the years 2,000 and 1700 BC, it was expanded.

Ultimately, it developed into one of the earliest significant urban centers and ports in the Aegean civilization. It had direct connections to the Minoan civilization. Akrotiri was deserted due to an earthquake circa 1500 BC, and it was utterly devastated by volcanic material.

The Babylonian Map of the World (900 B.C. – 700 B.C.)

This tablet has cuneiform writing as well as a distinctive map of Mesopotamia. It is an early portrayal of the world—through the Babylonians’ eyes. Assyria, Elam, and other locations are also mentioned. Babylon is in the heart (the rectangle on the upper part of the circle).

A circular watercourse bearing the name “Salt Sea” encircles the core region. The sea’s outermost rim is enclosed by what were likely once eight regions, all denoted by a triangle with the labels “Region” or “Island” and the distances between them.

The Divje Babe Flute (50,000 B.C.)

This early instrument is fashioned from the femur of a cave bear. Holes have been drilled into it with flute-like separation and placement. Some archaeologists think Neanderthals created it, and it may indeed be the oldest musical instrument ever discovered.

It dates back about 50,000 years. The discovery of this artifact created a shift in the perspective of Neanderthals. As a result, people began to view Neanderthals less as vicious, primitive brutes and instead as beings capable of independent thought.

The Pyramidion of The Black Pyramid of Dashur (1820 B.C.)

The highest point of the pyramids and obelisks contained the pyramidion. It’s a stone block that has a pyramidal shape. It represented the spot in which the solar deity Ra, also known as Amun-Ra, stood as the gathering spot of heaven and earth atop the monument.

This particular one was found beneath the ruins of Dashur’s Black Pyramid of Amenemhat III. Amazingly, the engravings on all four sides of The Pyramidion of The Black Pyramid of Dashur are readable and the object is in generally fair condition.

The Lycurgus Cup (4th century A.D.)

This is the sole intact specimen of a very unique sort of glass described as dichroic—that means the glass changes color if the cup is held against a light. When light is shined through the opaque green cup, it changes to a dazzling translucent crimson.

Small quantities of colloidal silver and gold are present inside the glass, giving it its peculiar optical characteristics. Around 1800 AD, when it was first constructed, a gilt bronze border with a foot was added. The British Museum purchased it in 1957.

Oldowan choppers (1.8 – 2 MYA)

Between 1.8 and 2 million years ago, early humans fashioned choppers from basalt. These tools, from the Oldowan stone tool culture, were discovered in Tanzania’s Olduvai Gorge, after which the sector was titled. These choppers were intensively used for daily tasks.

They are assumed to have been used for “cutting, chopping, and scraping” vegetables and animals. Homo habilis, a progenitor of Homo sapiens, invented these tools. Comparable artifacts were found all over eastern, southern, and central Africa, but the first of these implements were found in Tanzania’s Olduvai Gorge.

Bronze bells from the tomb of Marquis Yi (433 B.C.)

Marquis Yi was buried in his four-room tomb, in the year 433 BCE, together with his most valuable treasures. There were bronze weapons, complex jars, chariot fittings, and, most notably, a massive collection of bronze bells that were assembled into a unified musical instrument.

It probably required the cooperation of five people to perform. The bronze bells were possibly the most significant symbol, indicating that the Marquis would possess everything he needed to be content and happy in his afterlife. Also, there were 21 young ladies among them.

The grave of Richard III (25th August 1485)

An archaeology team from the University of Leicester unearthed these royal remains in 2012. From 1483 till his demise in combat in 1485, he reigned as king of England. It is a great achievement of contemporary science in recognizing skeleton fragments.

And, rightfully so, the tenacity of those dedicated people who had gone out to locate them was discussed all over the world. The tale of the grave, in which the king had been buried for more than 500 years, was lost in the din of media coverage, though.

The Madaba Map (565 B.C. – 560 B.C.)

The Madaba Map is not located on a sheet of parchment. Instead, it is a component of a meticulously crafted mosaic floor that is now an element of the Church of St. George. The Holy Land and its surrounding areas were included when the chart was initially conceived.

That was in the second part of the sixth century C.E. The Madaba Map is unquestionably the earliest map of the Holy Land, despite older ones having been found. The map is amazing not because of its age, but rather because of how accurate and detailed it is.

The Alfred Jewel (9th century A.D.)

The Alfred Jewel is a stunning example of goldsmithing that is built around a cut rock crystal slice. The inscription “AELFRED MEC HEHT GEWYRCAN,” which translates as “Alfred ordered me to be made,” links the jewel to King Alfred the Great (who reigned from 871 to 899).

This makes it an extremely important royal artifact. As per the Ashmolean Museum, the jewel had originally been a component of an aestel, or pointer, which was a tool often used to track the text in manuscripts. The jewel is an important work of Anglo-Saxon goldsmithing.

The Trundholm Sun Chariot (1400 B.C.)

This object belongs to the Early Bronze Age or roughly 1400 BC. It was found in Denmark. It represents the sun’s endless voyage by showing a celestial horse hauling a lavish gold disc while everything is on wheels. It was made using the “lost wax” technique.

That technique involves entirely encasing an incredibly detailed wax figure with a clay core. Wax melts during the final firing of the piece, creating a void that can be later refilled using molten metal. The Sun Chariot’s horse’s back is damaged, exposing its internal clay core.

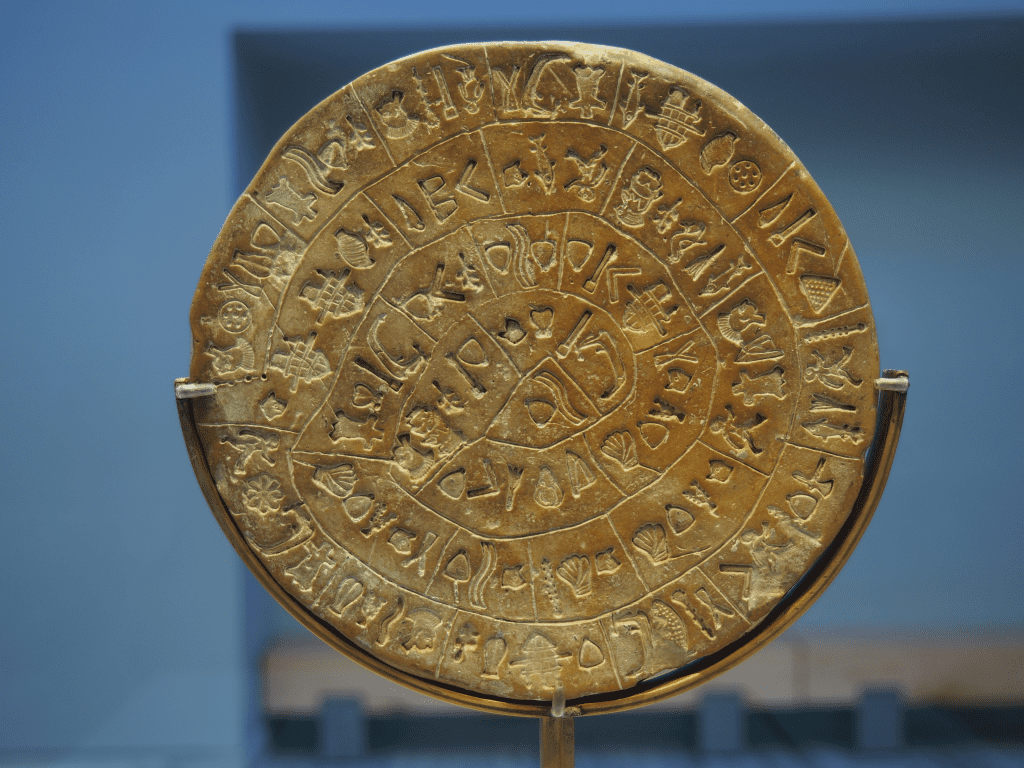

The Phaistos Disc (1900 B.C. – 1700 B.C.)

This disc of burnt clay disc is most likely Minoan in origin. It has a diameter of about 16 cm and is imprinted on both surfaces with 242 characters arranged in a spiral pattern. This particular archaeological discovery is still an unsolved mystery.

The disc was found in 1908 in the Minoan Phaistos “Old Palace” (c. 1900–1700 BCE) on the island of Crete. Very little is understood with any particular degree of confidence about the disc, and researchers disagree regarding its origin, manufacture, purpose, and meaning.

Sydney rock engravings (3000 B.C.)

Indigenous Australians carved figures into the rocks between Sydney and the Central Coast for tens of thousands of years. These actions have produced distinctive rock art. The Hawkesbury River, where this was discovered, serves as the border between Sydney and the Central Coast region.

The imagery of revered spiritual entities, mythological ancestral heroic characters, numerous endemic species, fish, and numerous footprints (mundoes) are among the images found in these indigenous rock engraving sites. Most historians concur that they date to the late Neolithic era, between 3000 and 4000 BC.

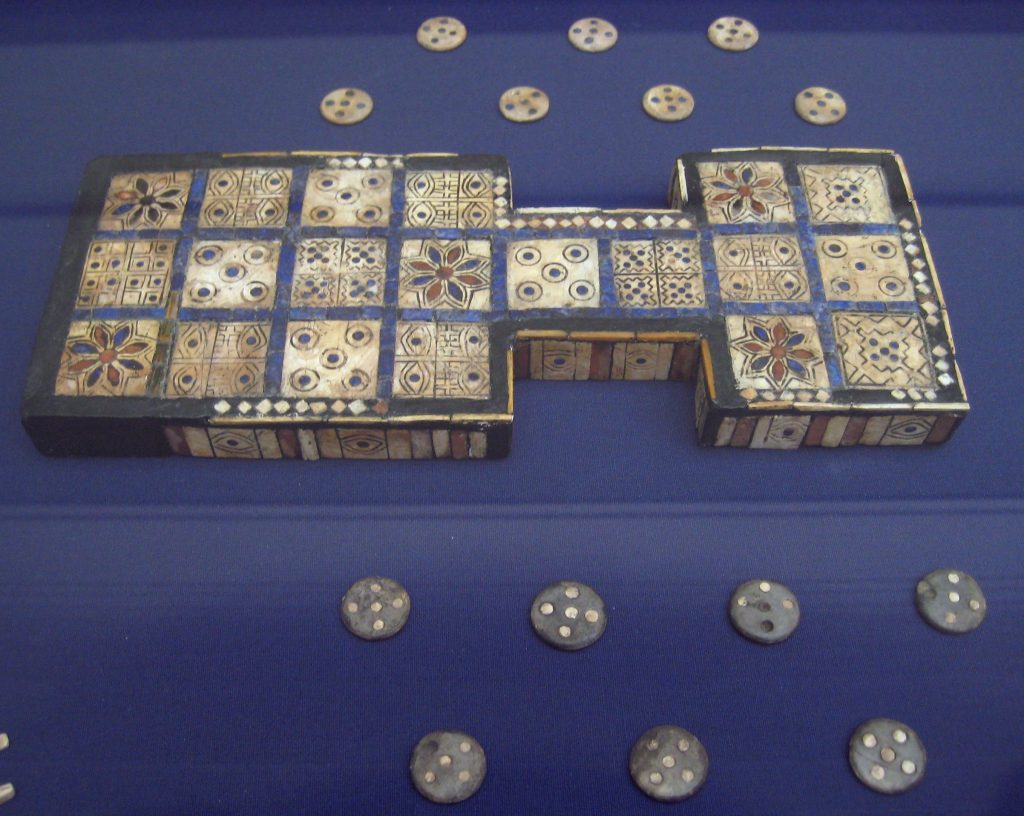

The Royal Game of Ur (2600 B.C. – 2400 B.C.)

During the third millennium BC in ancient Mesopotamia, a two-player strategy racing board game known as The Royal Game of Ur was invented. Individuals from all socioeconomic classes enjoyed engaging in this activity throughout the Middle East. Needless to say, its popularity was immense.

Also, game boards have been discovered as far apart from Mesopotamia as Crete as well as Sri Lanka. This particular specimen is among the world’s oldest game boards and is housed by the British Museum. It is traced to somewhere between 2600 and 2400 BC.

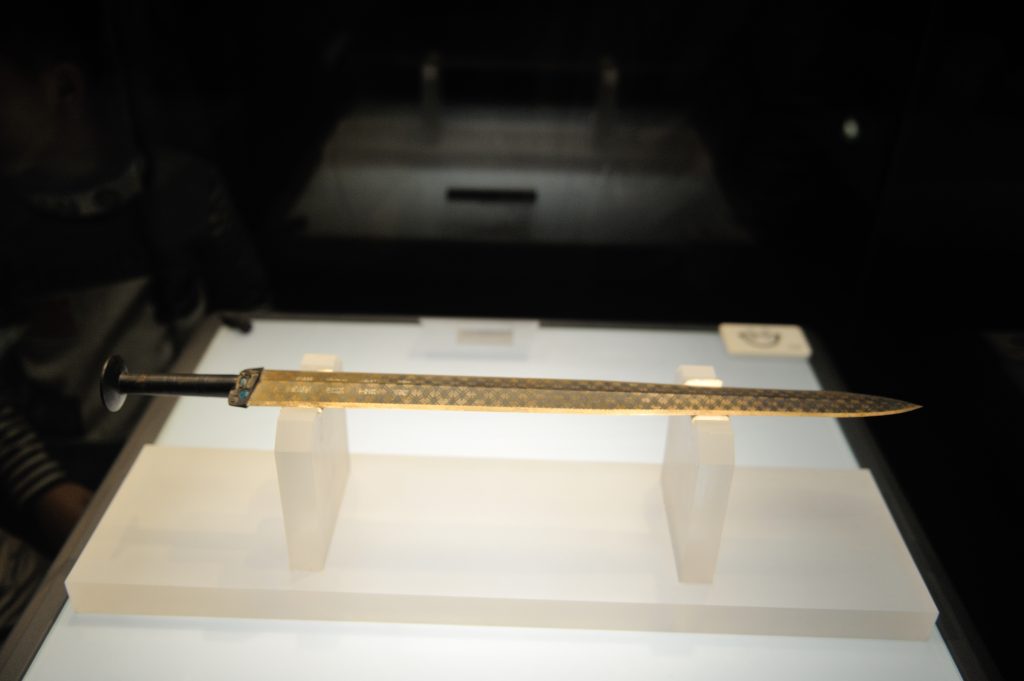

The Sword of Goujian (771 B.C. – 430 B.C.)

The old sword fits in the scabbard virtually airtight thanks to its black lacquer finish. This, combined with the sword’s chemical makeup, kept the majestic blade nearly tarnish-free and preserved its outstandingly sharp edge. Some have referred to the blade as “razor sharp.”

That may be exaggerating things, but the Hubei Department of Culture said it could easily cut through “20 pieces of hard paper.” The ancient lettering, known as “bird-worm seal script,” has eight characters inscribed on the blade that says, “King of Yue… made this sword for [his] own use.”

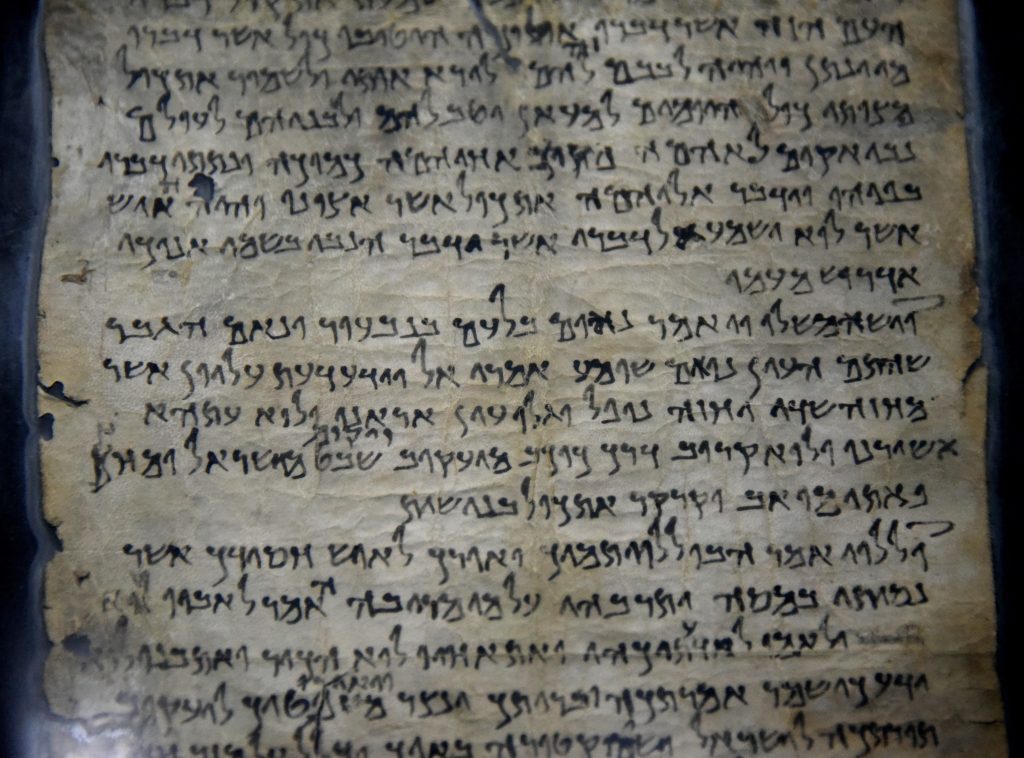

Dead Sea Scrolls (300 B.C. – 100 B.C.)

Many people believe that the Dead Sea Scrolls represent the most important archaeological discovery of the 20th century. Thousands of scroll pieces were found in the caves close to Qumran, which is situated on the northwest side of the Dead Sea, between 1947 and 1956.

Teams of academics stitched together all these scrolls throughout the following decades to create an incredible collection of manuscripts spanning from the third century B.C.E. until the first century C.E. The arid Qumran climate protected the manuscripts, which were kept in strong clay jars.

Olmec stone head sculptures (1200 B.C. – 400 B.C.)

The Olmec stone head sculptures from the Gulf Coast of Mexico (1200 BCE–400 BCE) rank as the most enigmatic and heavily contested ancient relics. Due to their distinctive physical characteristics, the widely accepted hypothesis would be that they depict Olmec kings.

There’s also the effort and expense required in their production and their distinctive physical attributes. One of the earliest civilizations to inhabit Mesoamerica was the Olmec. All of the pieces show men with intricate headdresses made of fabric and feathers, whether smiling, acting indifferent, or displaying frightening expressions.

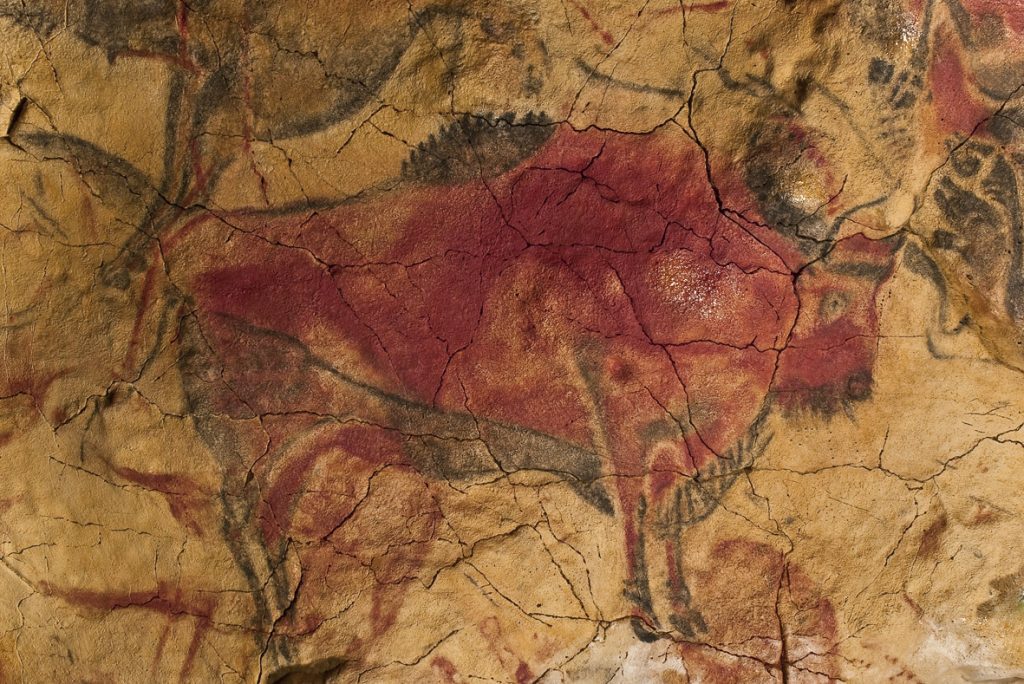

Altamira (18500 – 14000 years ago)

Prehistoric paintings can be found in Altamira, a Paleolithic cave in Santillana del Mar, Cantabrian area, northern Spain. In addition to Paleolithic cave art, the cave has remnants of the everyday routines of the past community because it was occupied for thousands of years.

In 1985, UNESCO designated it a World Heritage Site. The traces of human hands may be seen in the Paleolithic drawings, which were made with charcoal and organic Earth dyes. The artworks include bison, horses, deer, horses, and aurochs (a type of extinct wild cow).

Sutton Hoo (6th – 7th century A.D.)

Sutton Hoo contains an Anglo-Saxon king’s grave or cenotaph. Undoubtedly one of the finest Germanic graves ever discovered in Europe, the burial site shed new light on the connections and wealth of early Anglo-Saxon monarchs by containing a ship outfitted for something like the afterlife (but without a body).

The unearthing of it in 1939 was noteworthy as ship burial was uncommon in England. Within the mound, archaeologist Basil Brown found the remains of a long-dead Anglo-Saxon lord as well as the wreckage of an 86-foot-long (27 m) ship filled with treasure.

The Moai (11th to 17th centuries A.D.)

The Moai statues are among the most intriguing and well-known monolithic monuments in the entire world. They are found in the isolated Chilean region of Easter Island, and they depict the early inhabitants’ secret history and passion with rock carvings.

As a result of extensive study on these well-known sculptures, numerous broken and collapsed statues have now been refurbished all across the island. The figures’ heights range from 6 feet (2 m) to more than 30 feet, with gigantic heads perched on top of long torsos (9 m).

Caral-Supe (2600 B.C.)

Would you believe that there are gigantic pyramidal buildings as ancient as those in Egypt in the Americas? That’s true! Around 2600 B.C., when the earliest Egyptian pyramid was built, an outstanding ensemble of ancient architectural styles was adapted in the central coastal Peruvian city of Caral-Supe.

Caral is regarded by archaeologists as one of the biggest and most intricate urban centers ever constructed by the earliest recorded culture in the Western Hemisphere. In the third century BC, Caral had around 3000 inhabitants. To help complete the picture, a quipu with the town’s history was also found there.

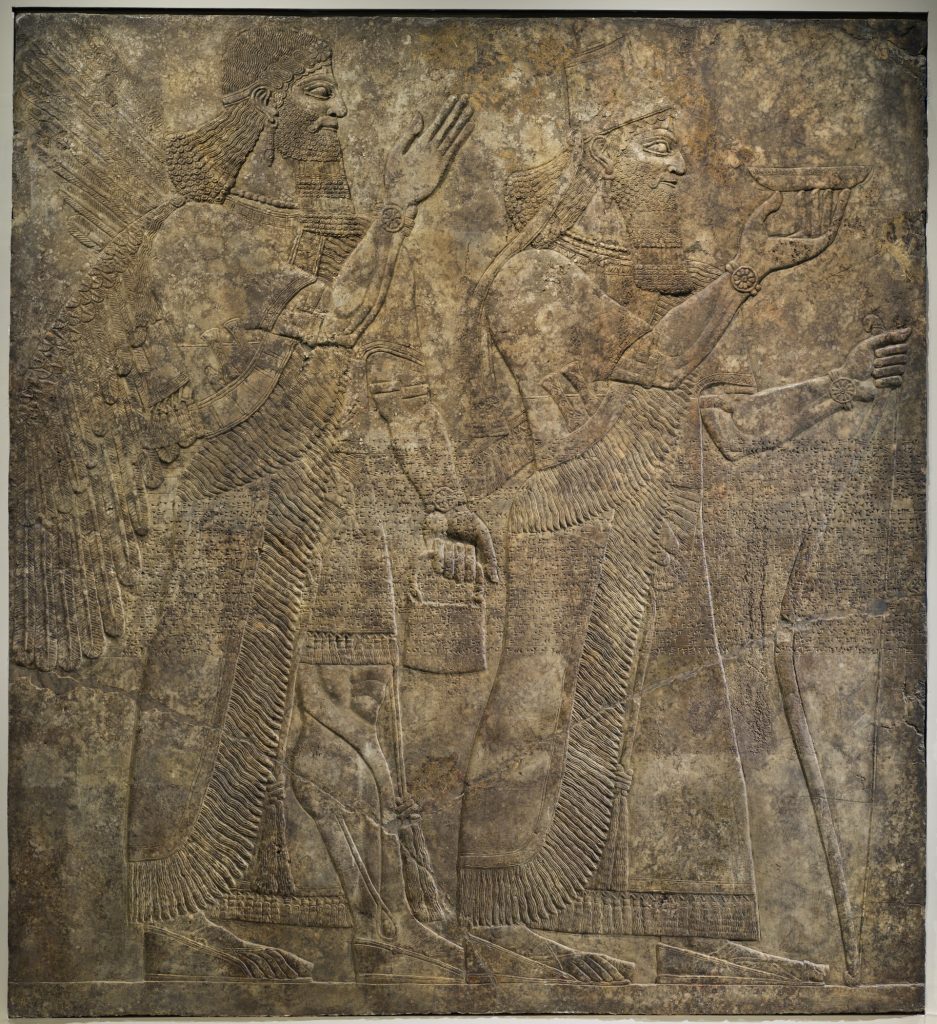

An alabaster relief from the Palace of Nimrud (9th century B.C.)

This absolutely stunning King Ashurnasirpal II sculpture, now on display at the Louvre, originally adorned a portion of an unbaked brick wall in the Assyrian palace of Nimrud. This architectural style was established by Assyria in the ninth century BC.

The king’s distinctive trademark is a truncated cone with something like a smaller cone protruding from the center as well as a lengthy “streamer” flowing from its back. Sadly, news sources in April 2015 said that Nimrud’s palace had been demolished.

The Ubaid artifacts (5000 B.C.)

The Ubaid era, which is unique to Mesopotamia and spans roughly 5500–4000 BCE, is a prehistoric timeframe. The time period predates the commencement of civilization linked with ancient Sumer by a significant amount. Academics believe that Sumerians are responsible for the development of society.

They were unearthed by archaeologists in Iraq. These strange artifacts depict human-like people with lizard-like traits, such as almond-shaped eyeballs, elongated heads, lengthy, slender features, and a reptile nose. Some people appear to be donning shoulder padding on their helmets.

The Pesse Canoe (8040 B.C. – 7510 B.C.)

The earliest boat ever discovered is a dugout canoe that was uncovered close to Pesse. A facsimile was used in a test to demonstrate that it remained sturdy in the water since there were questions about whether it had actually been a watercraft.

A local farmer discovered the Pesse canoe in 1955 while the A28 highway was being built. This ancient vessel was carved out of a scotch pine log using an axe some 10,000 years ago. It is 44 centimeters wide and three meters long.

Gerzeh beads (3200 B.C. – 3000 B.C.)

Experts have now shown, after a lifetime of debate, that perhaps the iron utilized to join 5,000-year-old Egyptian beads actually originated from a meteorite. In 1911, the nine tiny beads were discovered in a tomb in Gerzeh, an ancient Egyptian graveyard.

Early chemical analysis revealed nickel residues, which led researchers to postulate that the objects were constructed of meteoric iron rather than naturally occurring Earth elements. These beads, treasured as rare relics, were linked together to form a necklace with priceless gems like gold and carnelian.

Göbekli Tepe (11,000 years ago)

Göbekli Tepe, which had been hidden for 10,000 years, was unexpectedly rediscovered in 1994. Klaus Schmidt, a German archaeologist, was consulted for his knowledge, and what he discovered complicated our conception of mankind. The amount of skill and precision is what first catches the eye.

A wide variety of animals, including foxes, birds, boars, and snakes, are carved in detail and built in impressive structures made of limestone. One of the most noteworthy aspects of Göbekli Tepe is the T-shaped limestone stones that line the site’s stone circles.

The Lydenburg Heads (400 A.D. – 500 A.D.)

Karl-Ludvig “Ludi” von Bezing, a little child, spotted fragments of several enigmatic heads in 1957 while frolicking in the fields on his father’s farm near Lydenburg, Mpumalanga, South Africa. A few years down the line, he went back to the region.

It took several years for him to gather the fragments of seven heads. The Lydenburg Heads are a significant discovery on a global scale. They are one of the earliest types of African sculpture in Southern Africa. According to researchers, the heads are likely constructed for aristocrats or kings.

The Staffordshire hoard (650 A.D. – 675 A.D.)

The greatest Anglo-Saxon treasure trove was uncovered by an individual as he was operating a metal detector inside a freshly plowed field. The Staffordshire Hoard, assessed at well over £3 million, was acquired for the benefit of the general public. This was accomplished after an extraordinarily successful widespread appeal.

Currently, the Stoke-on-Trent City Council, along with the Birmingham City Council, share ownership of the impressive hoard. Around 4,000 pieces make up this amazing collection, including almost 13 pounds of gold, almost 4 pounds of silver, and about 4,000 cloisonné garnets.

Liangzhu jade cong (3300 B.C. to 2200 B.C.)

“Cong” is the term given to a form of jade with an unidentified use that has been discovered in Neolithic tombs in Southeast China. The cong has a circular hole and a rectangular cross-section. A common decoration for congs is a visage with two horizontal bars over it.

That stands in for the hairline, as well as a shorter bar below, which represents the nose. Among the tallest remaining congs is this one. These took a long time and effort to make as jade cannot be split; it must be handled with abrasive hard sand.

The dagger of Bush Barrow (2000 B.C.)

Among the most spectacular Bronze Age discoveries in Britain is the Bush Barrow dagger. Bronze serves as the material for the blade, but tiny gold studs are put in a zigzag pattern to embellish the handle. Since the craftsmanship was so detailed, children most likely completed it.

The majority of the gold studs on the dagger handle are only about one millimeter long and as fine as human hair. The object was covered in almost 140,000 tiny gold studs. The production location of the Bush Barrow dagger’s hilt has long baffled archaeologists.

Palace of Knossos (1950 B.C.)

The Minoan Civilization, among the most illustrious civilizations in human history, was centered most prominently at Knossos. The biggest and also most characteristic archaeological site ever found in Crete is the famous ancient city with the palace. It is believed that it served as the ruler Minoa’s residence.

In addition to being the home of the royal family, it served as the regional administrative and religious hub. Captivating legends like the fable of the Labyrinth and the Minotaur and the tale of Daedalus and Icarus are also associated with the Palace.

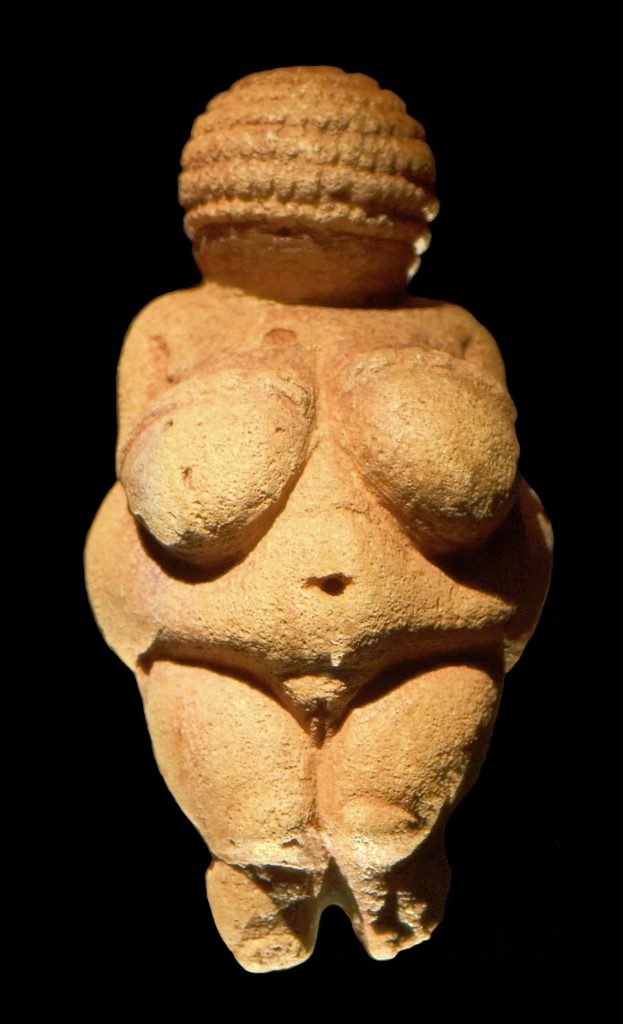

The Venus of Willendorf (between 24,000 B.C. to 22,000 B.C)

Among the earliest and best-known remaining masterpieces of art, the Venus of Willendorf relic is dated between about 24,000 and 22,000 B.C.E. But what exactly qualifies as a piece of artwork? The idea of “art” entails using talent to produce something with a basic understanding of aesthetics.

The item is not simply manufactured. It is designed with the goal of including aspects of beauty. Considering how old the figurine is, that’s an impressive feat. The figure was found in 1908, about one week into the Willendorf II digs in Austria.